Opinion of Judge Hays on Slavery in California (1856)

A Suit for Freedom in California.

Is a Slave Freed by Taking Him Into a Free State?

Opinion of Judge Hays.

Before Hon. Benj. Hays, Judge of 1st Judicial District, California.

At Chambers, Jan. 28, 1856, on Habeas Corpus.

In this case, the benefit of the writ of habeas corpus is sought for fourteen persons of colour, namely, Hannah (aged 34 years), and Biddy (38), and their children, to wit: Ann (17), Lawrence (12), Nathaniel (10), Jane (8), Charles (6), Marion (4), Martha (2), an infant boy (two weeks)—all children of Hannah; Mary (2 years), child of said Ann; Ellen (17), Ann (12), Harriet (8)— children of Biddy.

The petition states that they are free, having been brought into the State of California in the year 1851 (in the Fall, it seems), by Robert Smith, who has resided here with them ever since, and now holds them in servitude, and is about to remove to the State of Texas, carrying them with him into slavery. The defendant's return to the writ alleges that, in Mississippi, he owned as slaves Hannah, Ann, Lawrence and Nathaniel, and Biddy and her three children above named; he left that State for Utah Territory; Jane was born in Missouri (Illinois?), Charles in Utah Territory, and the other four in California.

They left Mississippi with their own consent, rather than remain there, and he has supported them ever since, subjecting them to no greater control than his own children, and not holding them as slaves; it is his intention to remove to Texas and take them with him; Hannah and the children are well disposed to remain with him, and the petition was filed without their knowledge and consent; "it is understood," he adds, "between said Smith and said persons that they will return to said State of Texas with him voluntarily, as a portion of his family."

All were brought up by warrant, except Hannah, who was shown to be sick, Lawrence engaged in waiting on her, and Charles, absent in San Bernardino County, but within this Judicial District. The case was submitted, as if all were present, under the statute, and judgment rendered on the return, in substance, that all said persons are free; and, for their greater safety, those under twenty-one years of age were placed in custody of the Sheriff of this County, as special guardian, except Charles, who was by a warrant placed in like manner in charge of the Sheriff of San Bernardino County; other orders were being made to secure this temporary disposition from any unauthorized interference. The two mothers were also finally put under charge of the Sheriff of this County, for their protection. The reasons for this decision were given fully, with which, it is just to him to add, the defendant then seemed to be content.

The case has since come up again upon the report of the Sheriff, and affidavits, showing cause for a warrant of attachment, which was accordingly issued against one Hartwell Cottrell, belonging to defendant's party now on the move for Texas, for contempt in attempting to induce two of said minors to leave the Sheriff's custody, etc., and upon his answer to that charge.

In order to avoid misconception in any quarter, it may be proper to review the grounds of said decision, and of the present proceeding. The question is mainly of fact, because the law is plain.

The argument in favour of Smith, at the trial, did not rest on a right, as their owner, to take these persons to Texas. The right is expressly disavowed by him. They did not come here before the admission of the State into the Union, and, if they had, the law has expired which provided for the deportation of persons of colour in that predicament. No such right could be set up under the Constitution. "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, unless for the punishment of crimes, shall ever be tolerated in this State" (Art. I. § 18).

An enactment of the sovereign people, which at once emancipates every slave introduced into the State voluntarily by his owner. We are, therefore, relieved from the distressing embarrassments of former cases, arising out of the struggle of the Legislature and the Courts to reconcile the letter of the Constitution and of the system of municipal law which it superseded with the comity considered to be due to our brethren of the slave States. We have carried comity—and it may have been a sense of duty—to the full length towards the sister States of the South. Whatever may be said of other free States, there is no reasonable cause of complaint against California. Having done so much for compromise and harmony, the Courts may now fall back upon the Constitution, and maintain it in full vigour, to the extent of their jurisdiction.

Although, then, there ought to be no difficulty in the matter in hand, it is not to be disguised that, in some vague manner, a sort of right is asserted over at least a portion of the petitioners. It is styled a guardianship, likened to "patriarchal" rule, and by a few strenuously insisted upon—so much so as to incommode and obstruct a public officer in the discharge of his duty.

The history of slavery, as displayed in a portion of the Union, is seldom the dark picture painted by fanaticism. There is no reason to dispute the kindness of the defendant in his former treatment of the petitioners, as their master; nor does it appear that the two parties have not since lived agreeably together. They have doubtless been of mutual advantage here; and their labour, which he has enjoyed, probably remunerated him for the "support" given them; at any rate, as he must have had everything his own way, he might have been well remunerated, looking at the urgent wants of this country for domestic servants. On this score, their accounts may be deemed fairly balanced.

It may be admitted that he has the ordinary qualifications, and, under other circumstances than the present, might be the guardian of those under twenty-one years of age. If he were going to continue his residence in California, he might retain the care of them; and, perhaps, receive unmolested the fruits of their labour, as others are doing with Indians, and, occasionally, with persons of colour—for, in default of a good law of apprenticeship, the law of guardianship has been liberally construed in this section of the State. Still, a legitimate guardianship, duly restricted, he could not demand of absolute right.

Such is the confusion hanging round this anomalous claim, that, in passing, the law governing this subject may be referred to more distinctly. The mothers of these minors would be entitled to their guardianship, "if competent to manage their own business, and not otherwise unsuitable" (Comp. Laws, p. 155, § 5). No guardianship, in itself, is so sacred as this. There must be strong reasons to disregard the claim of nature, even with persons of the class to which the petitioners belong.

"But," it is said, "they have not consented to this petition; on the other hand, their free and anxious wish is, to accompany the defendant in his new migration." This is the gist of his return, and none will say that it ought not to be scrutinized closely; none will say so who have had any experience with this class of people. Such a proposition—implying a deliberate desire to return to slavery—ought to be established to the highest degree of certainty. It is not consistent with our knowledge of the human heart. Remember, it is not the gratification of mere feeling that is involved, but the dearest interests for life, and for unborn generations, of fourteen persons, all of them minors, save two, and these last possessing very imperfect capacity, and till now little aid, to comprehend their interests or their rights. Their condition invokes the tenderest consideration of those who have to administer the laws, and, in truth, invites the sympathy of all generous men. Much that pertains to this inquiry has been acted in the presence of the Court by the parties, and could not be overlooked in forming a judgment.

Before proceeding further, we should bear in mind the statute of this State concerning the crime of Kidnapping. (Comp. Laws, p. 646, § 54, 55.) It is the chief means provided by the Legislature to preserve inviolate the personal liberty of the inhabitants. The crime is so repugnant to the ideas of modern civilization, that it is presumable every slave State stamps its perpetrator with ignominy. The punishment is, confinement in the State prison not less than one, nor more than ten years, for every person kidnapped, or attempted to be kidnapped. The offence is consummated in two ways—by force or by fraud.

It is done under section 54:

First, by "every person who shall forcibly steal, take or arrest any man, woman or child, whether white, black or coloured, or any Indian, in this State, and carry him into another country, State or territory;" or,

Secondly, "who shall forcibly take or arrest any person or persons whatsoever with a design to take him out of this State, without having established a claim according to the laws of the United States."

Section 55 reads as follows:

"Every person who shall hire, persuade, entice, decoy or seduce by false promises, misrepresentations, and the like, any negro, mulatto or coloured person, to go out of this State, or to be taken or removed therefrom, for the purpose, and with the intent to sell such negro, etc., into slavery or involuntary servitude, or otherwise employ him or her to his own use, or the use of another, without the free will and consent of such negro, etc., shall be deemed to have committed the crime of kidnapping and be punished," etc.

Undoubtedly, those over twenty-one years of age may be indulged their caprice as to their destination in the absence of force or fraud. It does not necessarily follow that they can make their children victims of such caprice. If a woman might deliberately surrender herself to slavery; she could not carry her offspring to the same fate. It is the first grand thought of the Constitution—

Where, then, is the evidence of "voluntary" consent, on the part of any of the petitioners?

The presumption—rather the direct proof—to the contrary, arising from the existence of the petition at all, is not rebutted by the mere asseveration of the defendant. Both petition and return had to be under oath; thus resulted an issue for trial. If advantageous for him to show that the petition was filed without their consent, it could be no hardship to devolve, as the law did, on him, the duty of shewing it affirmatively. They were before the Court, and could have been publicly called upon in person. They had been kept a day of more from intercourse with any who could influence them—an arrangement calculated to be more prejudicial to them than to him, for it left them isolated from even the kindly glance of sympathy. And their confinement (necessarily) in the public jail—as they could not comprehend the reason— might well have inspired them with distrust for their applications, and drawn from their fears an answer favourable to his objects. If there was other proof, that they had hinted to one human being their dissent from the petition, he ought to have offered it; no such testimony was produced, and it is to be inferred that there was no legal proof against the petition, and the speaking silence of the petitioners.

Such temerity in the neglect of proof is a striking incident in this trial, and suggests that reliance has not been entirely on the administration of justice, in its ordinary course—an idea encouraged by another occurrence on the second morning, that is not to be passed by unnoticed. This was a motion to dismiss the proceedings, based on a note from the petitioners' attorney to the attorney on the opposite side, in these words: "I, as attorney for the petitioners, being no longer authorized to prosecute the writ, and being discharged by the same, and the parties who are responsible to me, decline further to prosecute the matter." The author of this note being subpœnaed and examined, deposed that the affiant to the petition, stating that he had been threatened by some person (whose name was not disclosed) requesting him to abandon the suit; affiant originally promised to pay $500; the attorney agreed to do so, upon the affiant's securing him $100, in addition to the $100 already paid him by the affiant; but the attorney had not advised with the petitioners themselves, and had not informed them of this, or consulted their wishes.

Subsequently [unclear] filed a brief of his argument in the cause. The motion was overruled. Any citizen can understand how disastrous it might be to his rights and interests pending in the courts, if such a precedent in an attorney were approved and practised on. No attorney can desert his clients at his own pleasure, without good reason therefor, and fair notice to them. The payment of a fee by a third person does not constitute him a party to the suit. However charitably inclined to aid the real parties in this proceeding, the affiant was not one of the parties, and had no more to do with it than any other stranger, particularly after the writ had been executed, the parties all before the Court, and the cause in progress of trial. As well might the witness before a grand jury assume to dismiss an indictment for felony.

It is possible—yet strange, if possible—that the defendant had nothing to do with (to say the least) an ill-advised stratagem to frustrate the beneficence of this writ. His attorney for him denied anterior knowledge of it. He had the benefit of the denial, in one view that might have been taken of it. In itself—if he were believed to have been privy to it—the act would be incompatible with an innocent intention. It has too much the air of force. It gives room for a painful suspicion. If a respectable attorney could so far forget himself, when morally certain that force was at the bottom of it, what should we not expect to find operating amongst persons of a degraded caste, once slaves, ignorant of our laws, without money and almost without friends, their fears and hopes alike at the mercy of one they had ever looked up to with implicit obedience?

Thus much may be said: Whatever wish they might have to appeal for redress to the Courts, would, for the most part, be concealed from the defendant, and very cautiously communicated to those who might assist them. It would be prudent, in a degree, to "keep their own counsel." Nothing wonderful, if their exigencies made them play the hypocrite—they who have the name of free for eight years now past, still remained slaves practically to every intent and purpose. But not a whisper from them indicative of a willingness to go with the defendant has there been an effort to prove—menace only and force! It might be asked, Where were the numerous members of his family or his neighbours, if the sequel did not admonish that it would have been exceedingly dangerous to have had recourse to such witnesses, with an exercise of the right of cross-examination belonging to the vilest criminal? An extraordinary cause in a land where all are proclaimed free, and where the panoply of the law covers the weak and the poor, alike with rich and strong. Extraordinary, indeed, if the complaining voice of lawful freedom cannot be heard, to which the magnanimity of no slave State I am acquainted with would altogether turn a deaf ear.

Under such circumstances, let us look into the return, this being the sole evidence on his behalf.

It is remarkable that he does not pretend that Biddy and her three children are "well-disposed" to remain with him. They are excluded from this "voluntary" arrangement; he cannot, therefore, reasonably claim any further control over them. If Hannah only is "well-disposed," Biddy must be averse and opposed to it, by his own showing. The petition, then, has the unequivocal consent of four of the petitioners from the tacit admission of his return. And it has been shown that none of the children of Hannah can be lawfully conveyed by her into a state of bondage. Any third person had the right to file the petition for them (Comp. Laws, p. 167, § 1, 2); and it would be folly to talk of "consent" on their part. This is a broad step towards clearing up the mystery.

How about this distinction between the mothers? Why is Hannah so "well-disposed?" Why is Biddy so reluctant? How is it with Biddy, in fact? She is the oldest of the petitioners. For the purpose of testing the state of her mind—after the course pursued by their attorney—a question was framed, and, with defendant's acquiescence, addressed to her, the judge only and two disinterested gentlemen, Hon. Abel Stearnes and Dr. J. B. Winston being present. (B) Hannah is entitled to Biddy's answer: "I have always done what I have been told to do; I always feared this trip to Texas, since I first heard of it." Laying no stress on her further answer, for its intrinsic weight—"Mr. Smith told me I would be just as free in Texas as here"—why has she "feared this trip to Texas?" Instinct must have taught her that she might be made a slave; very little reflection could be necessary to discover it.

Now, did defendant never tell them what Biddy says? Must it not have been discussed often and again in this family? Is it not the very subject they would most naturally talk over day in and day out? When Smith himself declares, "It is understood between us that they are not to be slaves, but only members of my family" (for this is the substance), what does it mean, if it does not mean that he had promised them they would be "just as free in Texas" as here? This understanding could hardly be effected by a pantomimic scene between the parties. On Biddy, it is clear, the artful promise made no impression. And, looking at their intimate relations, in a common servitude, this important fact does not argue much for the truthfulness of his statement as to Hannah. Every hope must meet a kindred terror in their hearts. Why, then, conduct so different? On such a point, skepticism is a virtue. Charity may hesitate to accuse of wilful perversion; Justice will not blindly confide in unsupported representations. Be it said in his favour, She may have yielded to over-persuasion, and importunity extorted a semblance of conviction, construed to authorize his oath to consent; this is all. Never was she so completely deceived—not, if there be faith in maternal instinct. What is the power to lull and quiet apprehensions of a future so dark? How forget the experience of Slavery? There is the glorious instinct of Freedom! a bright torch ever to simplicity the most credulous.

The evidence, on the trial, does not tell precisely what influences have been brought to bear most upon her. Some things strongly point to actual duress; and, if a little bent by persuasion, the force of a feather might seal her lips. Turning from any harsher feature of the transaction, it is impossible to overlook that gentler violence— of over persuasion—so visibly at work amongst the petitioners, and which, with its purpose, is as utterly odious as physical force. The question is now narrowed down to Hannah. Conceding the utmost claimed, as to her consent, she is but the victim of a fatal delusion. No man of any observation in life, will believe, that it was ever true—this pleasant prospect of freedom in Texas! Her inclination at times has been as represented—she has been egregiously imposed upon, in her ignorance, by "false promises" and "misrepresentations;" the whole truth has been steadily concealed from her. Surely, this view does not improve the defendant's cause. Whether he has dealt most in this flattering illusion, or others have aided to fasten it upon her mind, can make no difference: the man Cottrell has been a clever adviser—and one of the most unscrupulous.

The dubious inquiry of her daughter Ann—"Will I be as free in Texas as here?" shows that craft had left some trace of the mischief which it failed to accomplish with the mothers, and evinces at the same time the mode of its operation. Hannah was not present at the trial, so as to speak for herself. From the evidence of the Sheriff (C), with the additional light derived from Henderson, Barnes and Carpenter, it is palpable that the petition had her knowledge and assent from the beginning. The cold replies when sickness at length permitted her to appear are accounted for, and, if she tells the truth, a humiliating spectacle is exhibited; and whether she be credited or not, as to the immediate cause of her hesitancy—not her silence (for her very hesitation spoke a volume)—she is entitled to be listened to when, breathing freer, she declares that she never wished to leave, and prays for protection.

To force her, or any of them, into the measure proposed, would be the detestable crime already defined. For justice to be essentially administered in the case, the act of habeas corpus furnishes ample remedies in the discretion which it confers (§ 16, 17) and which includes the powers exercised by Courts of Equity in the like circumstances.—Forsyth on Infants, § 60, 63, 64, 66, 78, 83.

To these principles resort was had in the judgment rendered, and the orders and process consequent thereon: which there is every solid reason for adhering to, until the petitioners can become settled and go to work for themselves—in peace and without fear! It is proper to add that, if there had been this petition or writ, the testimony, as the record now presents itself, would require the same dispositions, while it might call attention more closely to the bearing of the criminal laws upon the facts. It ought to satisfy him, to have held these petitioners as slaves, in fact, for so long a period, since they became free by his own voluntary act; without asking the privilege of removing them, against their will and the policy of our laws—as he would remove his cattle—to a State where their chance for freedom, in the precarious situation in which they will be placed, may be about as good as that of the dumb beasts which bear them on the journey. Can it be expected that the Courts will connive at and tolerate this wretched speculation?

The opinion entertained touching the intent of the defendant has been plainly intimated, and as mildly as the nature of the case will admit. Born and educated in one slave State and having always since resided in another, until I came to California, I ought to appreciate the kindly attachment that grows up between master and slave—a feeling often warmer and more durable with the [unclear] meanwhile where is self-interest? With not an over share of the world's goods (it seems some $500 and an outfit), and his own white family to maintain—is there not a stronger impulse beneath his "patriarchal" complacency, to incur the cost and toil of taking this number of negroes through a wilderness of two thousand miles? Still, it is not so important to distinguish the predominant motive, as to see the inevitable result of his conduct on their rights. Even without a bad intention, a man is not to be permitted to do a positive injury to others, when it can be prevented.

It is worthy of notice that those of the petitioners who were not born in Illinois, Utah Territory and California, originally came with defendant from Mississippi. They cannot be returned there as slaves, because the laws of that State prohibit the importation of slaves. If misfortune, or mere disappointment, drove a man from California—how natural to seek again the hearthstone and smile of old acquaintance and friendship! But, here would be a serious obstacle, if the aim were profit and gain. On the other hand, the laws of Texas forbid the importation of free negroes. These petitioners, therefore, cannot be lawfully carried there, as free. From the very beginning he could only hope to keep them—and must so hold them out to the world—in the character of slaves and nothing but slaves. If scruples of conscience opposed, he would be constrained to see them sold, for remaining within that State beyond the time fixed by law (probably six months).

Turn what way they may, the nets of legal chicanery, or of policy (if you please), are open to receive them; it being not the frailest cord to hold them—as may be imagined—that "if a slave voluntarily return to the domicile of his master, the laws of his domicile, and the state of slavery reattach" (2 Cal. Rep., 441). Did it never occur to him that he alone, not they, can possibly profit by an exposure to such dangerous experiments? And all these children, peradventure soon scattered to the four winds—when shall they begin to think of rights erewhile their own, from whose memory will have faded the very name of California! How hazardous to tamper with liberty! Well he knows what a mountain of obloquy and prejudice the injured slave must scale, to gain freedom. Nay, blame not the deed of "patriarchal" sincerity! Nevertheless, time will pass, and bring its varied changes in the cherished circle around him; and sad reverses may baffle his purest plans. He asks too much power. 'Tis a fearful temptation he courts, to do wrong himself; and for his children after him, to perpetuate what may never be made right—if it could be successful now.

If we may turn aside to contemplate the "signs of the times," and endeavour to foresee the destined course of agitations that shake the sacred altar of national liberty to its base—how long before stern necessities of the white race, unto the end of self-preservation, shall have forged heavier chains for the bondsmen of our country. Men may not everywhere, nor always—even now they do not—reason and legislate so justly us in the past days of sounder counsel and better feeling. They may not abide in moderation and wisdom, like the Supreme Court of Louisiana, in the interpretation of the precise language contained in our own Constitution.

"It warns owners of slaves in other States, removing into Ohio, to sell or leave them behind, if they are not intended to be emancipated, and promises emancipation to all slaves brought in, or permitted to be brought in, on their masters entering the State with the view of fixing their domicil in Ohio. . . . . .

"The Constitution emancipates, ipso facto, such slaves whose owners remove them into that State with the intention of residing there; the plaintiff having been voluntarily removed into that State, by her owner, the latter submitted himself with every member of his family, white and black, and every part of the property brought with him, to the operation of the Constitution and laws of the State; and, as according to them—slavery could not exist in his house—slavery did not exist there; and the plaintiff was accordingly as effectually emancipated, by the operation of the Constitution, as if by the act and deed of her former owner. She could not be free in one State, and a slave in another; her freedom was not impaired by his forcibly removing her into Kentucky to defeat her attempt to assert her freedom, nor by her subsequent removal, voluntary or forced, into this State." (2 Martin R., N. S., 401; as to Illinois, 2 L. R. 483.)

"Preventing justice is preferable to punishing justice"! This question is not to be deferred to the tribunals of other States. The lawful liberty of the humblest dweller on our soil, is a thing too precious to be left the sport of every contingency in human affairs. It is the duty of the Courts to see that the interests of these parties are properly guarded, and, above all other considerations, to provide that, under no specious pretext whatsoever, they are conveyed into bondage. Whatever prepossessions a man may have on the political or social controversies of the day, no true sentiment of "State rights"—if he reflect well—will consent to an evasion and violation of the Constitution of his State; all should have pride enough to wish to keep unimpaired the integrity of our own institutions—until, if to be, we can adopt better.

(A) A. J. Henderson.—"Defendant told me, in a private conversation, that several persons had offered him to help to get the petitioners by force—did not say whether he had consented thereto, or not; this was since the trial."

Jas. M. Barnes.—"I have lived with Smith, defendant; his three sons said, 'if their father had their grit, they would have the negroes that were taken from him on habeas corpus lately.' Defendant has started for Texas, with Whitney, Cottrell, and others; since the trial, Cottrell said, 'if Smith agreed, and she would go, he would take Ellen'; and Whitney said, 'it was right that Smith should have the negroes.' I understood them to allude to Hannah, Biddy, Ann and Ellen; if they can get their consent, they intend to take them on this trip, and are all now in Los Angelos, with the intention of looking round and feeling to see what the negroes have to say in relation to going. He sold his cattle for $2,000 and has about $500 left."

Dr. A. H. Cooper.—"To-day, Cottrell & Meredith came to the house of Robert Owen, a coloured man, where the petitioners had been placed by the Sheriff; they repeatedly asked Ann and Ellen to go, stating that the wagons were ready; that they were as free as any one; that the judge had perjured himself by not having discharged them; that Smith did not want to take them away to bondage, and was not going away—he wanted to have them as well situated as when with him; if they wanted to go they should go, and if any one objected to it let him come forward, and they would show that they should go. When about leaving, Cottrell said, 'Old man Smith has plenty of money.' The other spoke up, saying, 'Yes, and by G—d he will see them out with it—he is not done with it yet; tell old Bob, if he has not anything to do with it, not to have, or he will be sorry for it.' Later, Smith's son came and took Ann out, and had a long conversation with her. Since, I met Cottrell and Smith's son returning to the house." (The petitioners, upon this, were removed to the jail.)

F. J. Carpenter.—"As jailor, am entrusted, by the Sheriff, with seven of the petitioners, under age; last night found Cottrell and Smith's son at the jail; they brought a bottle of brandy for Ann; from their manœuvres, believe they came to carry off some of the children."

Answer of H. Cottrell.—Denies intention to persuade off petitioners; merely wished to take them to see their old mistress, who is in bad health and wishes to see them before leaving. The family are all reconciled to the disposition that has been made in the matter by the Court. I was out of the house when Meredith said—"Old Smith will see it out"; also heard him say—"Old Bob will be sorry for it"; he was drunk, or he would not have said it. I told the girls, yesterday, that if they wanted to go to Texas, as Mr. Smith had laid in provision for them, and they were free, they could go, according to law, as I thought—I did not say positively—I asked them to go out to the rancho—I don't think I asked to urge them to go to Texas with us—if I did, I forget it. I told her these words: The Sheriff tells you to stay here; if you start, it will be time enough for him to come forth and make his objections; I do not know whether you have the privilege of going or staying! I am one of the teamsters; if I go home to-night, we will start to-morrow (Sunday). (The Court remanded him to the custody of the Sheriff; having been allowed to go at large till Monday, he did not return!)

A. H. Cooper.—"Last Saturday, about sunset, Joseph Clark said to me that I must go to —–'s shop, and withdraw the affidavit made by me in this case—(above)—that it must be settled that night on Southern principles, or I would suffer for it. I told him the affidavit contained the truth. He then said: 'No one but a d—d Abolitionist could have made it, and there is a gang here joined together to swindle Smith out of his negroes.' After much violent abuse he jumped off his horse, saying: 'You are a d—d Abolitionist, too, and I would as soon blow your brains out as not.' He got his pistol half out—I stepped into the house. He then mounted his horse, saying, 'G—damn you, I will settle it with you before morning.' He then rode away. Last year he was a constable. Mr.——– has said nothing to me. The object, I believe, was to intimidate me from appearing as a witness."

(B) Biddy.—"I have always done what I was told to do; have always feared this trip to Texas, since I first heard of it; Mr. Smith told me I would be just as free in Texas as here; I do not wish to be separated from my children, and do not in such case wish to go. Ellen answers, she is willing to go whithersoever her mother goes; Ann says she wants to stay where her mother stays. Ann, daughter of Hannah, answers, that she does not wish to leave her child, and they knew her mother would rather die than go and leave her children. She asks as follows: 'If I go back to Texas, will I be as free as here'? And being told by the Judge that she might not be, she answers: 'I cannot say now whether to stay or go; I want to stay where my mother Hannah stays—if she stays, I want to stay—it is hard to be scattered so.'" (Responses to question of the Judge on January 18.)

(C) Testimony of Sheriff.—"On the 24th instant, and again on the 25th instant, Hannah told deponent, that before she had been brought before the Judge (January 22), she had been compelled by the family of Robert Smith, and particularly by the wife of said Smith, to take an oath that she would state in Court, that it was her desire to return to Texas; and now she wanted to tell me, as Sheriff, that such was not her real desire, but she wanted to stay in California and be protected by the law and the Courts; having taken such an oath she felt compelled to observe it, and would have done so, if brought up in Court again, but it was not her wish to return to Texas. She requested me to see the Judge this morning, before she would be brought into Court, and explain her situation to the Judge. She did not state directly whether Robert Smith thus compelled her to take such an oath or not; the impression left on her taking [unclear] is that his wife most insisted upon and had appeared but once, to wit, January 22.

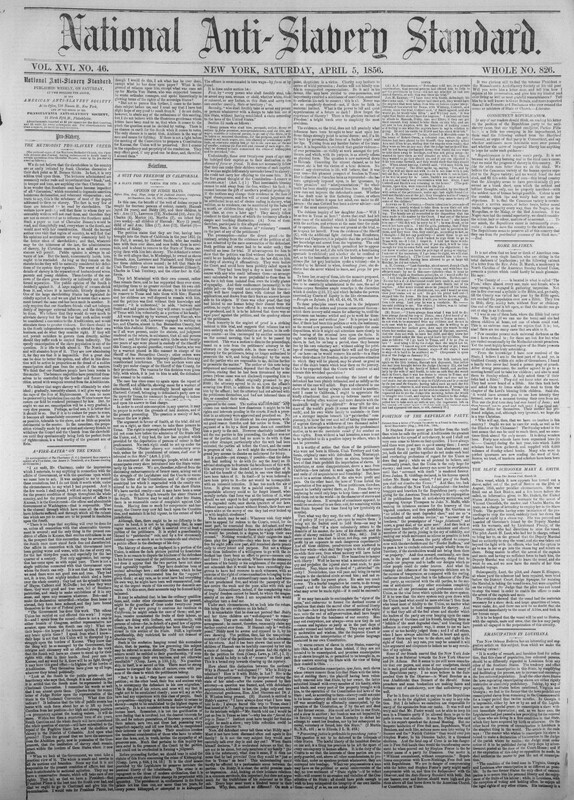

- Title

- Opinion of Judge Hays on Slavery in California (1856)

- Description

- In the decision in this case, a California judge ruled that Biddy Mason and her three children, as well as a woman named Hannah and her nine children and grandchildren, were "free forever" after their enslaver brought them into the free state of California to reside. The judge's opinion was published in the official newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

- Date

- 1856-04-05

- Document Type

- Newspaper

- Document Category

- Primary Source

- Bibliographic Citation

- National Anti-Slavery Standard, April 5, 1856

- Contributor

- Kevin Waite

- Title

- Opinion of Judge Hays on Slavery in California (1856)

- Description

- In the decision in this case, a California judge ruled that Biddy Mason and her three children, as well as a woman named Hannah and her nine children and grandchildren, were "free forever" after their enslaver brought them into the free state of California to reside. The judge's opinion was published in the official newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

- Date

- 1856-04-05

- Document Type

- Newspaper

- Document Category

- Primary Source

- Bibliographic Citation

- National Anti-Slavery Standard, April 5, 1856

- Contributor

- Kevin Waite