Making A Sioux Indian Into An American Citizen (1916)

Making A Sioux Indian Into An American Citizen.

To learn that 186 Sioux Indians may now claim the rights of American citizenship, may vote and fight and pay taxes for their country's sake and do other things equally prideful or necessary sets the average man to thinking rather gravely.

The rights of the red men is a subject of peculiar interest to the Secretary of the Interior, Mr. Lane, who represented the government in the ceremony admitting these Indians into citizenship. Upon his return from the reservation recently he seemed to take pleasure in discussing his policies in the matter and relating the unique ceremony in detail.

The Yankton reservation in South Dakota is the home of about 2,000 Sioux, who have been living there for fifty years, on the edge of the Missouri river. Though coming from the more warlike tribes, these natives never give any trouble. In fact, the fiber of the race has been breaking down on account of our orphan asylum attitude toward nearly all our Indians.

Thrown upon their own resources, they would become economically independent. Those that are competent should be free from supervision. And in accordance with this idea I created a competency commission and told the members to go through the Yankton reservation and see who could look after their own affairs.

* * *

About 100 who were found to be competent did not want to make application to share in all rights of the paleface, because they would be taxed, and they 'preferred to have the United States look after their business, as it did this very well.' Many who held this view were men of substance.

Several farms I visited showed a number of fine horses. One or two farmers had autos. Still, they did not pay taxes to either county or state. On the other hand, many on the reservation had already made application for citizenship. Altogether, the commission found about 180 who were capable, whether desirous or no, of joining the ranks and rights of their white brothers.

These two classes of men and women were notified that they would be given full citizenship—that is, patents in fee—so they would have to look after their own loans. Before this policy was inaugurated in any large way I thought it best to go out there. I went directly to the agency, which is down on the bank of the Missouri river, and Saturday morning, which was the 13th of May, the Indians began coming in. There were all kinds of conveyances. There must have been thirty or forty automobiles and between two and three hundred carriages. Some red men came on foot. Every horse there was a good one. The land lies thirty miles from the nearest railroad, and it was a typical gathering of Indians. The finest-looking were full-bloods.

On a mound facing the river there was a tepee, and near that a tent and platform. The commissioners of the county and other officials were upon the platform, while the Indians were grouped around in front in a halfcircle, some standing, others sitting about on the grass. There were several hundred of them.

Here Secretary Lane called his secretary for what he termed the ritual on admission of Indians to full American citizenship, and said that he began the ceremony with these opening words of the ritual:

The President of the United States has sent me to speak a solemn and serious word to you, a word that means more to some of you than you have ever heard. He has been told that there are some among you who should no longer be controlled by the bureau of Indian affairs, but should be given their patents in fee and thus become free American citizens.

It is his decision that this shall be done, and that those so honored by the people of the United States shall have the meaning of this new and great privilege pointed out by symbol and word, so that no man or woman shall not know its meaning. The President has sent me papers naming those men and women and I shall call out their names one by one, and they will come before me.

* * *

Then I read the list of names, and those Indians came out of the crowd and sat in front of me. The last named was Joseph Cook, who had been a sergeant in the United States Army, a tall, splendid looking fellow. As I pronounced his name he and two of his fellows, Eagle Dog and Hollow Horn, came out of the tepee in full Indian regalia, with Sioux war bonnets and feathers.

Joseph Cook stepped to the front and the three of them sang, in the Sioux language, a song they had composed themselves, to the words of one of their Sioux poems, the refrain of which was, 'O great white father, make us to live and to see like the white man!'

Then I called Joseph Cook by his Indian name, which is Blackstone, and I gave him a bow and arrow and I said, "You are now to take up the life of the white man. You have shot your last arrow. That means you are no longer to live the life of an Indian. You are from this day forward to live the life of the white man. But you may keep that arrow; it will be to you a symbol of your noble race and of the pride you feel that you come from the first of all Americans."

He retired into the tepee and at once removed his Indian clothes, signifying the transformation from Indian life to that of the white man, and came out in ordinary dress. I led him then to a plow, which was standing on the grass in front of me, and I said, again using the ritual phrasing, "Take in your hand this plow. This act means that you have chosen to live the life of the white man—and the white man lives by work. From the earth we all must get our living, and the earth will not yield unless man pours upon it the sweat of his brow. Only by work do we gain a right to the land or to the enjoyment of life."

He did this very solemnly. There was not a smile on the face of one Indian in the gathering, in fact. I then gave Joseph Cook a purse and repeated the words: "I give you a purse. This purse will always say to you that the money you gain from your labor must be wisely kept. The wise man saves his money so that when the sun does not smile and the grass does not grow he will not starve."

* * *

Then we had a flag, and this was held by a pretty Indian girl, under a tree. She came forward with the Stars and Stripes and I said to Joseph Cook: "I give into your hands the flag of your country. This is the only flag you have ever had or ever will have. It is the flag of freedom, the flag of free men, the flag of a hundred million free men and women, of whom you are now one."

Then I passed it over to him and the others who had gathered round, and they all took hold of the flag, and I said: "The flag has [a] request to make of you, that you repeat these words:

"For as much as the President has said that I am worthy to be a citizen of the United States I now promise to this flag that I will give my hands, my head and my heart to the doing of all that will make a true American citizen."

Then I passed from one to another, and while still holding on to the flag I handed each a button which we designed for this purpose, an eagle bearing a flag, and said: "Now, underneath this flag I place upon your breast the emblem of citizenship, and may the eagle that is on it never see you do aught of which the flag will not be proud." As I did that, the crowd shouted: "Joseph Cook is an American citizen!"

Some women were initiated also, some of them in gorgeous, almost Parisian, gowns, though many wore shawls on their heads. As her white name was announced each of these women applicants came forward and was presented by the secretary with a workbag and purse and briefly told of the influence the white woman had in the home and the future of the nation of which she had now become a part.

A flag was given to each Indian woman so honored, and responses similar to those the men were required to make were repeated, while the little gold badge of citizenship also was fastened on her breast, the audience rising and shouting then that this woman, too, using her name, was now an American citizen.

Secretary Lane then gathered the new citizens in the schoolhouse, and organized a mutual co-operative association to protect them in their business affairs.

Linked resources

Items linked to this Document

| Title | Description | Class |

|---|---|---|

Native American Citizenship and Competency During the Allotment and Assimilationist Era Native American Citizenship and Competency During the Allotment and Assimilationist Era |

This teaching module explores how citizenship featured in Native American policy during the Allotment and Assimilation Era. It highlights the first formal naturalization process for individuals on a national scale. Focusing on competency commissions from 1915 to 1920, this unit guides students in analyzing how legal assessments of "competency" in the context of citizenship were shaped by race, gender, and settler values. Using primary documents— including applications, inspection reports, and naturalization rituals—this module examines how federal policies enforced whiteness and domestic norms as criteria for inclusion. The module also encourages discussion about the dual role of citizenship as both a tool of assimilation and a potential resource for Native resistance and legal agency. |

- Title

- Making A Sioux Indian Into An American Citizen (1916)

- Description

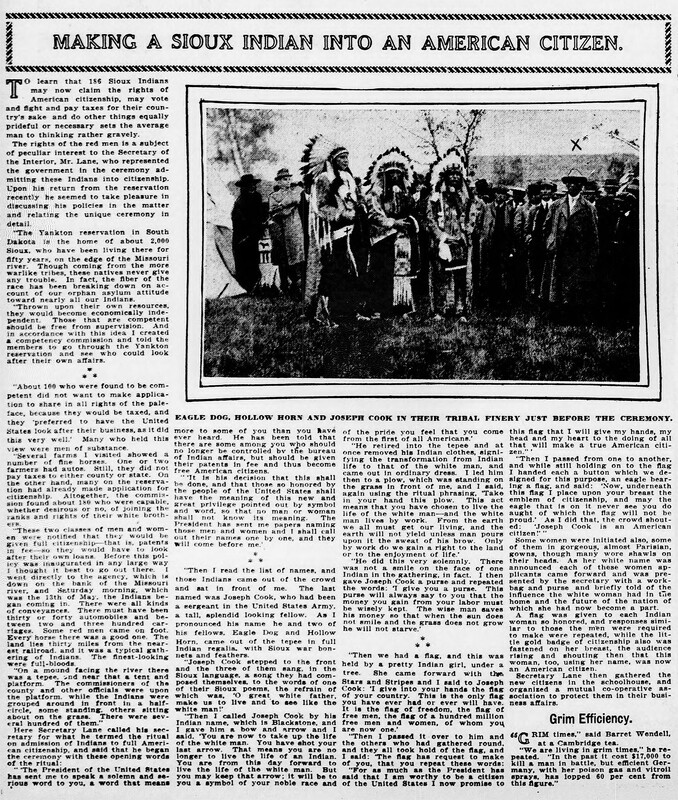

- In this newspaper article, Secretary of Interior Franklin Lane gives an account of a naturalization ritual that took place on the Yankton Reservation, South Dakota, in 1916. This article highlights the lived experience of naturalization processes for Native American individuals becoming U.S. citizens, revealing the involvement of other participants at the ceremony. This account highlights the complexities with receiving allotment for Native individuals and some of the effects citizenship had on legal and political rights. With a photograph of the event, this document provides a glimpse into the symbolic nature of the event, where the restructuring of Native identity encouraged in Allotment and Assimilation era policies is performed.

- Date

- 1916-05-28

- Subject

- Native Americans

- Temporal Coverage

- Territorial Expansion

- Jim Crow Era

- Exclusion Era

- Allotment and Assimilation Era

- Progressive Era

- Long Civil Rights Movement

- World War I

- Document Type

- Newspaper

- Document Category

- Primary Source

- Bibliographic Citation

- "Making A Sioux Indian Into An American Citizen," Evening Star, May 28, 1916

- Digital Repository

- Library of Congress

- Contributor

- Annabelle L. Lyne

- Title

- Making A Sioux Indian Into An American Citizen (1916)

- Description

- In this newspaper article, Secretary of Interior Franklin Lane gives an account of a naturalization ritual that took place on the Yankton Reservation, South Dakota, in 1916. This article highlights the lived experience of naturalization processes for Native American individuals becoming U.S. citizens, revealing the involvement of other participants at the ceremony. This account highlights the complexities with receiving allotment for Native individuals and some of the effects citizenship had on legal and political rights. With a photograph of the event, this document provides a glimpse into the symbolic nature of the event, where the restructuring of Native identity encouraged in Allotment and Assimilation era policies is performed.

- Date

- 1916-05-28

- Subject

- Native Americans

- Temporal Coverage

- Territorial Expansion

- Jim Crow Era

- Exclusion Era

- Allotment and Assimilation Era

- Progressive Era

- Long Civil Rights Movement

- World War I

- Document Type

- Newspaper

- Document Category

- Primary Source

- Bibliographic Citation

- "Making A Sioux Indian Into An American Citizen," Evening Star, May 28, 1916

- Digital Repository

- Library of Congress

- Contributor

- Annabelle L. Lyne